During AAPI Month, Financial Advice for a Poorly Understood Group

Why the term ‘model minority’ is harmful and other challenges for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders.

The term Asian American Pacific Islander, or AAPI for short, encompasses people with roots in the United States and whose ancestors originated from across Asia and the Pacific Islands, including countries such as China, Korea, Japan, India, Pakistan, Vietnam, the Philippines, Guam, and Samoa. In the 1960s, the term “Asian American” was coined as a political strategy to unite Asian American ethnic groups. It was a movement “fighting against not just anti-Asian racism but also racism and imperialism against all people of color,” relates Phuong Luong, a Boston-based certified financial planner whose practice includes East Asian American and Southeast Asian American clients.

Luong was born into a multigenerational household of Vietnamese immigrants in Brooklyn, New York. She received degrees from Dartmouth College and Boston University. After a decadelong career as a public school educator, Luong has been advising families throughout the wealth spectrum about their finances. Currently, she is the founder of Just Wealth, an independent registered investment advisor, and a contributor to Morningstar. In the middle of AAPI Heritage Month, we checked in with Luong about the special challenges this diverse group faces. Here’s what she said.

Leslie Norton: The Asian American and Pacific Islander designation isn’t one size fits all.

Phuong Luong: AAPI communities are a fast-growing demographic that cuts across all wealth levels and income levels, not just ethnicity and geographic diversity. There’s also temporal diversity regarding when folks came to the United States. Did they immigrate here by choice? Because of refugee status? Was it to seek better economic opportunity either from an impoverished status in their home countries or were they highly educated and recruited to work or study in the US? What was the political environment like for immigrants when they arrived in the US? Also, there can be lots of generational differences between older immigrants and second or third generations when it comes to comfort with US culture and financial systems.

Norton: Yet this community is often described as “the model minority.” What challenges are associated with this stereotype?

Luong: I learned about this term during my first career as a math teacher, during a lunchtime professional development training about Asian American history. It wasn’t until my 20s that I learned about this history. The term “Asian American” was coined to create solidarity between Asian and Asian American groups and with other people of color. The term AAPI came later to include Pacific Islander communities. And unfortunately, this term has been used by some who say “Look at Asian Americans, they’re all doing great economically. Why can’t you other people of color do as well as them? You should do what they’re doing to succeed.” It’s such a misguided, harmful belief, even to AAPI people who “benefit” from this.

The model minority myth can be limiting because the next part of that myth is that if you aren’t doing well, then you’re not behaving correctly or making the right decisions. As I’ve argued, there are structural and systemic reasons that people are economically oppressed in this country. Of course, your personal decisions can impact your chances of developing financial security. But it shouldn’t be a hero’s journey for people to get there.

Not a Model Minority

There’s also a myth that Asian Americans are good at math and school in general. I’ve had AAPI students who struggled at math and felt so bad about themselves because they absorbed the stereotype that math should come easy to them. I mentioned earlier that I was a math teacher. Actually, I wanted to be a reading and writing teacher. I applied to a dozen different schools but was only hired at one of them. Guess what role I was assigned to when I was hired? It was the only math teaching position I had applied to. I was grateful to have a job, so it wasn’t until years later that I wondered if the stereotype that Asian Americans are good at math influenced my trajectory.

Norton: Let’s talk about income inequality in this population.

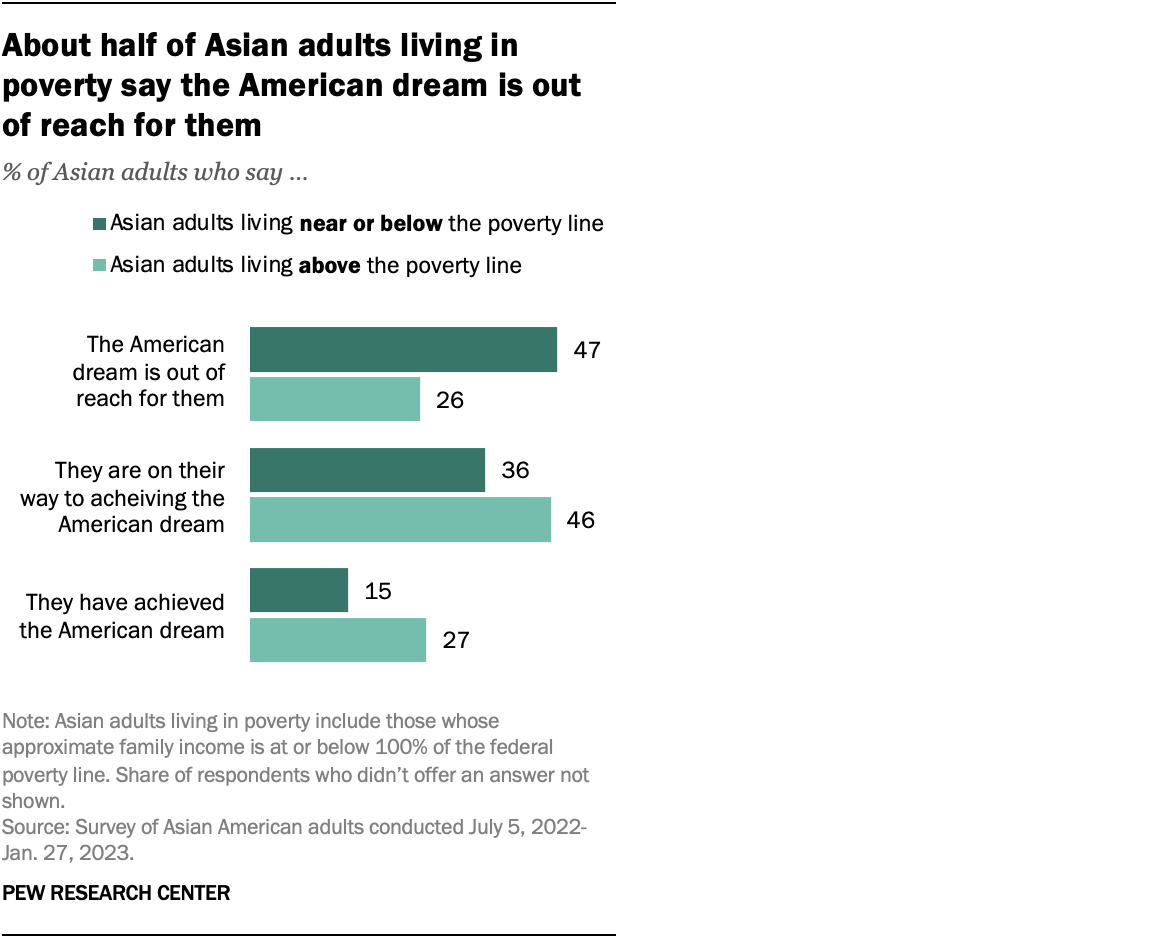

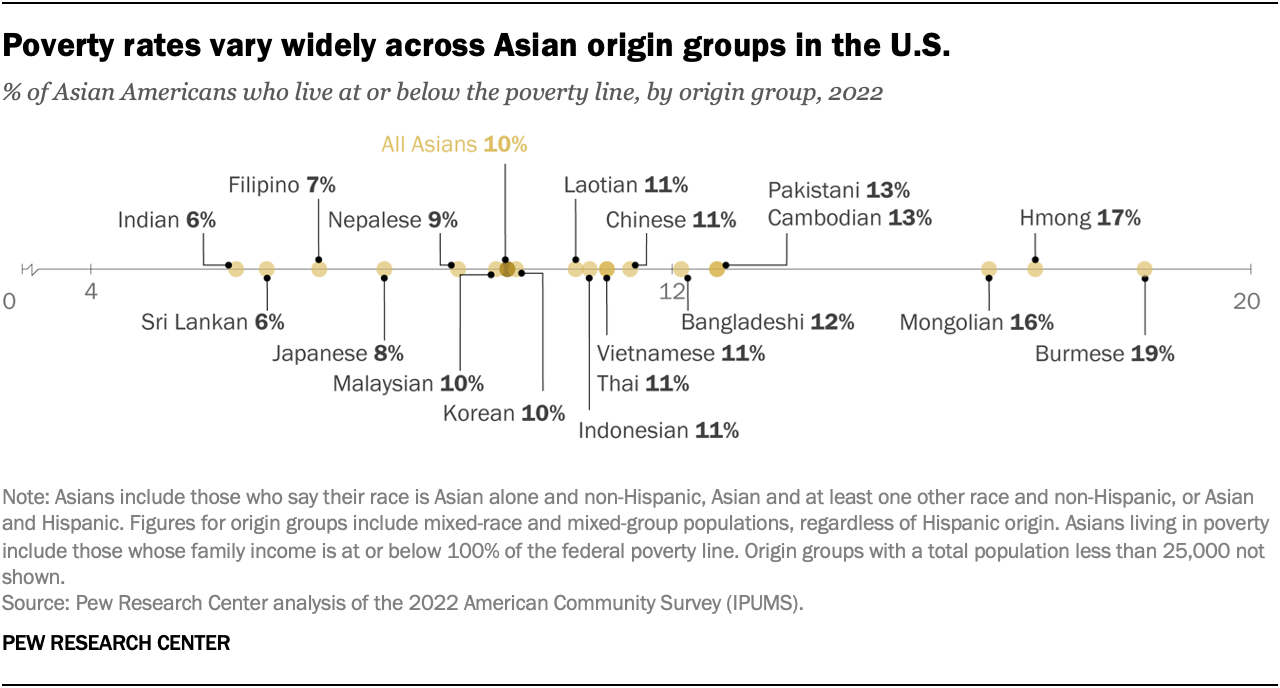

Luong: Income inequality is still increasing most rapidly among Asian American groups, compared to other demographics. Wealth gaps between the poorest Asian Americans and the wealthiest Asian Americans are still wider than gaps within any other racial group in the US. Vox has an interesting graphic explanation. I’m quoting from the National Community Reinvestment Coalition here: “In 2021, Asian Americans on average had a household size of 3.4, compared to the national average of 3.0. This larger average household size, coupled with the disproportionate concentration of Asian Americans in metropolitan areas where the cost of living is high, are important factors to understanding Asian American income more richly than the raw top-line statistics.” Meanwhile, about one in 10 Asian Americans, which is more than 2.3 million, lived in poverty in 2022.

AAPI Poverty Rates

Norton: What are some financial planning and investing and saving challenges?

Luong: How do we generalize without overgeneralizing? I’ve seen two things that groups within the AAPI demographic have in common. My bias and knowledge is toward Southeast Asian and East Asian experiences, but this may be generalizable across other immigrant groups as well because the immigrant story and the Asian American story are intertwined.

One is a mistrust of government and financial institutions and the stock market in general because of a history of financial seizures of assets in their family’s country of origin. I’ve seen that typically in older generations, but there could be a lingering sense of that in younger generations.

Two, a discomfort in talking about money cuts across so many demographics. That discomfort stems from a lot of different things: Financial trauma that’s happened, especially if people have grown up in poverty, because the model minority myth says, your family should be doing well. And the corollary, for an AAPI child, is that if your family isn’t doing well, that says something about you. That is a personal experience for me. I used to have a lot of shame around money because my family grew up with financial insecurity. I used to lie about it. I spent many years pretending in school and with friends that my family was middle-class because I bought into society’s messages that not being wealthy was a personal failing.

There could also be feelings of shame if they’ve achieved financial security. Because, as people of color, immigrants, or second-generation immigrants, there’s a feeling we should help others in the community. But how to maintain our own financial stability when there’s so much need out there? Some of my clients have worked with organizations like Resource Generation and Lunar Project to explore this question and build community with others.

Norton: Any other forbidden topics?

Luong: Family transitions such as divorce or estrangement can also be taboo topics in AAPI communities. Unfortunately, staying within a marriage or unhealthy relationship that’s not working can be a badge of honor in a lot of cultures. However, the stigma is breaking down. A colleague of mine, Thao Truong, a CFP, identifies as AAPI, specializes in working with women in transition, and is training to become a certified divorce financial analyst.

All this creates a heightened level of stress. Honestly, it’s personal and stressful for anybody to talk about their money. For many of my clients, speaking with me is the first time they’ve ever spoken to a financial planner or anybody about their money. And I’ve found that, when you let people talk, when you don’t judge them for their actions or circumstances, they open up and can make progress on what matters to them.

Norton: What are your top pieces of advice for Asian Americans and advisors who serve them?

Luong: I’ll start with general financial planning advice.

One, for advisors, learn the history of policies and economic oppression in the United States, because once you do that, it will show in your interactions with clients that you are not judging them. Our culture and society judge people based on their level of financial stability. So, I consistently must train myself to read and learn and talk about the actual data. This data point will surprise you: At least two thirds of the people in the US will experience poverty. They might start there and grow wealth, or start wealthy, move into a lower-income situation, and require public benefits. It can go both ways.

Clients, too, should learn economic history. It helps retrain people, thinking back to your childhood, to say that it wasn’t your fault, that it wasn’t your family’s fault. Once that shame can be cleared, I think that’s where a lot of progress can be made. I’m speaking about lower-income people now.

Two, find an advisor if you have specific questions where you’d like support. Many people may not feel comfortable talking to a professional. But there are professionals who support clients at various levels of wealth and income: nonprofit counselors, pro bono advisors, and hourly or retainer financial advisors. There will be someone out there who is a good match for your questions and goals. If you feel judged, or you don’t feel comfortable, it’s OK to find someone else.

Three, find a tax professional. A lot of my clients, and also my peers, think they can do it themselves. That’s part of the model minority myth. Your financial status can change dramatically over a lifetime. You can go from a lower income to a much higher income. Your tax situation can change dramatically when that happens. There can be big consequences if you’re not doing your taxes correctly or have tax planning strategies you’re not utilizing.

Four, understand your health history because it can have short and long-term implications for your financial plan including insurance, estate planning, and so on. Many AAPI families avoid talking about health because we don’t want to worry family members or save face. I’m in my late 30s. Health issues that affected our parents and grandparents are now starting to appear in my peer group. So often, when I’ve gone to the doctor, my doctor will say, “Have you talked to your family about this?” And I have to say no. We don’t talk about health issues. Every family is different, but I’ve seen this pattern happening, not just with physical health but of course mental health, too.

Norton: How about advice on saving?

Luong: What is the one thing people can do to get more control of their money? One, list out all of your assets, the cash, the investments, the real estate, and all of your debts including loans and credit cards and mortgages. Advisors call this a balance sheet. When you’re talking to AAPI communities, a household balance sheet might be multigenerational. During the first six years of my life, my household included my parents, siblings, two grandparents, and about eight aunts and uncles and their kids. It was in Brooklyn. And in lots of families, including my own, family members got financial help, either as a loan or a gift, to buy their first homes. Many folks, including AAPI people, are a part of the sandwich generation, meaning they are taking care of children while also supporting parents and/or grandparents.

Creating a balance sheet, let alone a comprehensive financial plan, when multiple family units are involved can be complex, but it’s an important start so you can assess where there might be opportunities to save, build wealth, or start estate planning. This is where advisors can bring value. For example, Jason Co is a fee-only advisor who speaks English, Mandarin, and Cantonese and has experience providing multigenerational financial planning.

A champion in the household can kick things off by saying, “Let’s get this organized. Let’s do this together.” The financial advisor can facilitate the conversion or coach the clients in leading the conversation with their family. It can get messy, it’s a lot of conversation, and it involves a lot of trust. You need a champion in the family to encourage these conversations so that folks can have peace of mind. Because that is what financial planning is all about.

Norton: Thanks, Phuong.

The author or authors do not own shares in any securities mentioned in this article. Find out about Morningstar’s editorial policies.

/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/IJKB5DGDNJFLPP6SBNF27R3UEA.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/VSMLFOHJRVBK5L2JAJXUPP274Q.png)

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/morningstar/ZNKQPGMG5RFE5GPV47XGWXDLMI.png)

:quality(80)/s3.amazonaws.com/arc-authors/morningstar/d53e0e66-732b-4d50-b97a-d324cfa9d1f8.jpg)